This week’s Torah reading of parashat Matot opens with the topic of solemn vows and oaths, their binding nature and the extent to which they can be annulled. In modern society the making of such oaths plays only a tangential role, so we tend to give it little thought. That does not mean that we cannot learn something useful from our ancient laws. After all, keeping one’s word and doing what one promises are important parts of civilised life everywhere—and this is the issue that underpins the making and breaking of vows and oaths.

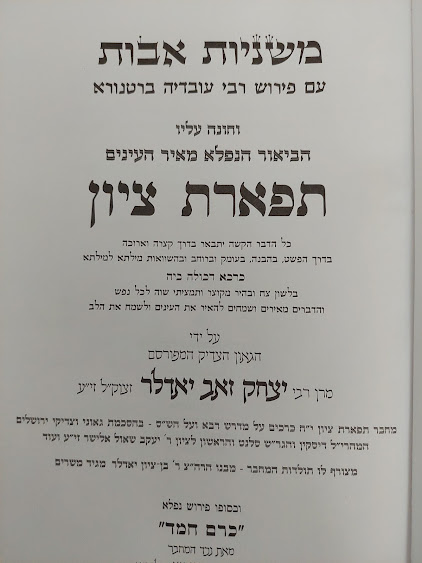

Not only the

Mishnah but the Talmud give considerable space to oaths, dedicating no fewer

than three tractates to them: Nedarim (defining a neder vow and its

application to vows concerning food and daughters), Nazir (on the making of

Nazirite vows and their consequences) and Shevuot (oaths made in the course of

commerce and litigation). But that is not all. Pirkei Avot mentions oaths too,

on three occasions:

·

“Oaths are a protective fence to abstinence”

(Rabbi Akiva, Avot 3:17)

·

“Don’t question your fellow at the time he is

making a vow” (Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar, Avot 4:23)

·

“Wild beasts come into the world on account of

vain oaths and desecration of God’s name” (Anonymous, Avot 5:11).

From debate

in the Talmud as to whether oaths are good, bad or both, we can see that much

depends on the circumstances and the manner in which people make them. At one

end of the spectrum we see how a person can strengthen his or her resolve to do

the right thing by making an oath to do so; at the other extreme we learn of

people taking God’s name in vain when making oaths that are without purpose or

meaning. There’s not much point in making an oath that a muffin is a muffin,

but at least that proposition is true. To utilise God’s name when swearing that

a muffin is not a muffin is an insult to human intelligence, whether one is

troubled by invoking God’s name in vain or not.

Of all

Rabbi Akiva’s teachings in Avot, “Oaths are a protective fence to abstinence”

is probably the one we encounter least frequently, since not only oaths but

also abstinence are very much out of fashion. There is however more to Rabbi

Akiva’s teaching here than meets the eye. Taking a positive view, his teaching

suggests that binding oral commitments like oaths and vows are clearly of value

if they help to strengthen the resolve of someone who is motivated to distance

himself from the pleasures and sensual experiences of the world—whether

permitted or otherwise—for the purpose of gaining greater proximity to his

Maker.

In the world at large, many people practise the popular institution of the New Year Resolution—a pledge to undertake the making of (usually) one major change in their lifestyle in order to produce some sort of improving effect. These resolutions often cover abstinence from substances that are pleasurably harmful if consumed in quantity (e.g. chocolate, patisserie, alcoholic beverages). Or they may relate to acts and deeds (e.g. making a greater effort to visit elderly relatives, or regularly clearing their email in-trays). One thing they generally have in common is that much of their power to bind the person making them depends on that person telling others that he or she has done so. This means facing shame and embarrassment if, having publicised a resolution, a person then admits in public that he or she has broken it.

Like New

Year Resolutions, the oaths and vows of Mishnaic times raised the expectation

that the person making them would respect and stand by them. However, unlike secular

resolutions, the oaths and vows that the Mishnah discusses were made by people

who, by invoking God’s name, reminded themselves that both their binding

commitment and any breach of it were made before their Creator, giving extra

power to the notion that it is important to keep one’s word and honour one’s

promises even if their subject, such as limiting their consumption of chocolate

and booze, affects non-one but themselves.

A further

note on abstinence and what it means should appear later this week.