We are only human and, try as we will to be clinically objective in our analysis of mishnayot in Avot, our opinions, biases, preferences and prejudices inevitably leak out.

At Avot 5:17 an anonymous mishnah teaches:

אַרְבַּע

מִדּוֹת בְּהוֹלְכֵי בֵית הַמִּדְרָשׁ: הוֹלֵךְ וְאֵינוֹ עוֹשֶׂה, שְׂכַר הֲלִיכָה

בְּיָדוֹ. עוֹשֶׂה וְאֵינוֹ הוֹלֵךְ, שְׂכַר מַעֲשֶׂה בְּיָדוֹ. הוֹלֵךְ

וְעוֹשֶׂה, חָסִיד. לֹא הוֹלֵךְ וְלֹא עוֹשֶׂה, רָשָׁע

There are four types among those

who attend the study hall. One who goes but does nothing—he has gained the

rewards of going. One who does [study] but does not go to the study hall—he has

gained the rewards of doing. One who goes and does, he is a chasid.

One who neither goes nor does, he is wicked.

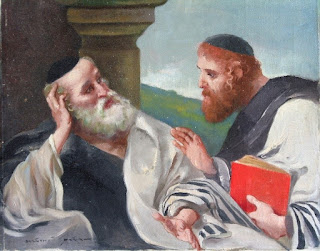

It is difficult to retain the flavour of the Mishnaic-era term

chasid when translating it into modern English. “One who is pious” is clumsy

and misses the mark because words like “pious” and “piety” have attracted in

today’s English an aura of sanctimony rather than sincerity. Left untranslated, the word chasid

conjures up images of ultra-religious followers of a rebbe, garbed in black

hats and long black coats and sporting sidelocks and beards.

Rabbi Shlomo P. Toperoff (Lev Avot) designates the chasid

as a saint. In doing so he has a precedent from the world of philosemitic

scholarship: the Reverend Travers Herford employs it in his The Ethics of

the Talmud.

The word ‘saint’ carries baggage: it may be deployed as a

term of approbation of someone’s righteous and selfless behaviour, often in the

face of temptation or with the prospect of suffering an enduring loss; it is

also frequently used in a highly sarcastic comment on a person’s

far-from-righteous behaviour. Rabbi

Toperoff was a pulpit rabbi in a town which then had two synagogues—one frequented

by serious Torah scholars, the other (the “Englische shul”, which was

his) being attended by more of the town’s rank-and-file population. The Englische

shul was looked down on by some of the members of the frum synagogue

who would likely not wish to hear his English sermons, and maybe it was this

that was his motivation for writing the following:

I personally doubt that any of the people who avoided going

to Rabbi Toperoff’s synagogue and hearing his sermons would have read these

words, but he does raise an interesting point: is there any real value in attending

a sermon when you doubt that you will learn anything new from it and are

confident that time spent engaged in other forms of learning would reap a greater

benefit? Gila Ross (Living Beautifully) may think so. As she observes:

“Rabbi Mendel of Kotzk points out

that the very act of pulling himself out of his comfort zone and going to a

place of learning is going to help that person focus on his spirituality”.

Pulling oneself out of one’s comfort zone is the key point

here. The very act is itself part of an ongoing process of character

development. Gila Ross does not quote Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai on this, but

in the second perek of Avot we see how, not once but twice, he orders his best

talmidim to leave the Beit Midrash and go out and see for themselves how people

live, to enable them to learn what best to do and what best to avoid.

For comments and discussion of this post on Facebook, click here