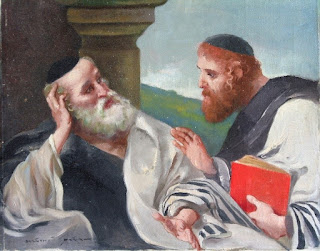

The brilliant, mercurial Rabbi Elazar ben Arach offers us three pieces of advice at Avot 2:19, one of which is this:

דַע מַה

שֶּׁתָּשִׁיב לְאֶפִּיקוּרוּס

Know what to answer a heretic.

How relevant is this teaching to us today? At a time when

religious observance was the norm and the notion of God’s existence was

generally beyond question, the apikoros (heretic) could be expected to

be well-informed and thoroughly versed in religious matters, and capable of

arguing the case against Judaism (or, for that matter, any other religion). To

take on an apikoros was no easy task: one needed mastery of the Torah

and of our extensive and complex prophetic literature as an absolute minimum.

Nowadays, as Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks once observed, the apikoros is

most likely to be someone who has neither knowledge nor interest in the

existence of God and the truth of the Torah. Cynical and likely to be hostile

to religion, he has no doubts to call his own, but to argue with him is to risk

generating doubts in oneself.

Rabbi Norman Lamm (Foundation of Faith, ed. Rabbi

Mark Dratch) uses this mishnah as the basis of an idea of his own—that, in our

portrayal of Judaism in contemporary society, we should be careful not to

create heretics. He writes:

“[W]e Jews ought to be so very

concerned not only by the impression we make upon outsiders, but by how we

appear to our fellow Jews who have become estranged from our sacred tradition. We

have labored long and hard and diligently to secure an image of Judaism which

does not do violence to Western standards of culture and modernity. But at

times the image becomes frayed and another, less attractive image is revealed… Sometimes

we have made it appear that we are barely emerging from the cocoon of

medievalism”.

This is a difficult line to take. Yes, we do try to portray

our Judaism as being compatible with the norms of contemporary society—but this

is not easy when that society is not hospitable to most forms of religious

practice and is quite sceptical regarding religious belief. We can’t pretend that the Torah only teaches things

that are woke or politically correct when we know it doesn’t. That’s why two

recent English-language books have proved so important. In Shmuel Phillips’s Judaism

Reclaimed (Mosaica, 2019) and Raphael Zarum’s Questioning Belief (Maggid,

2023), the authors are conscious of the need to address uncomfortable questions

in a lucid and respectful manner, seeking to explain the deeper meanings

contained in the Torah rather than rely on soundbites and rhetoric.

Rabbi Lamm continues:

“If we are to be witnesses to

Torah, then we Jews must have a more impressive means of communicating with the

non-observant segments of our people. Saadia Gaon pointed out a thousand years

ago that the best way to make a heretic, an apikoros, is to present an

argument for Judaism that is ludicrous and unbecoming. We cannot afford to have

sloppy newspapers, second-rate schools, noisy synagogues, or unaesthetic and

repelling services. When you testify for God and for Torah, every word must be

counted and polished!”

Does Rabbi Lamm go too far here? His citation of Saadia Gaon’s point is apt,

but how does he get from that to his conclusion? Do “noisy synagogues and

repelling services” create heretics—or merely people who are indifferent to

organised Judaism and its traditional rituals?

For comments and discussion of this post on Facebook, click here.